What forecasting taught me about learning

Working on forecasting stuff over the past few years made me think a lot about building and optimizing models. Eventually they started to make so much sense that I started to apply some of those same techniques myself in the real world outside of computers.

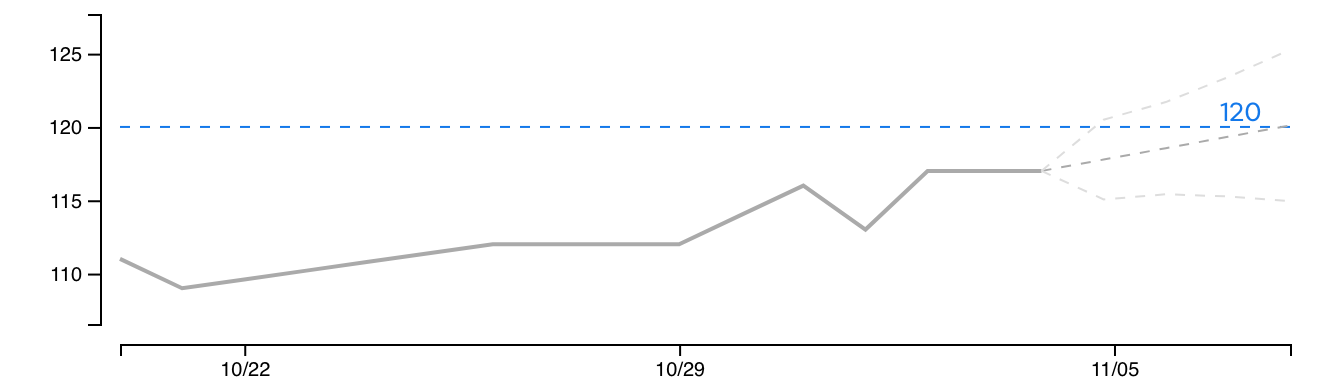

In the context of this post, forecasting means time series forecasting, which takes some amount of known data (solid grey in the image below) and predicts a future trend (middle dashed line) with some uncertainty (outer dashed lines).

An algorithm generated that forecast, and in the following sections I’m going to talk about the high level techniques and principles that algorithm used and how I like to apply them in real life.

Forecasting models don’t think about what’s right. They try to be the least wrong.

There are plenty of things in life that are too complicated to have a single right answer. Even with the time series forecast in the image above, there’s no single trend line that is “right” for the given data. So trying to find the right answer when it’s not even well-defined isn’t worth it. It’s much easier to move in the direction of being less wrong. Eventually you get to the right place, or somewhere good enough.

Example: What’s the best way to sell a product? Start by eliminating the approaches that don’t work so well.

Forecasting models try lots of different things.

If you want to be the least wrong, you need to consider and try lots of different approaches, and make sure you’re staying unbiased. Computers can only do relatively simple things compared to humans, but unlike us they can do those things incredibly fast. In the time series forecast above, the algorithm went through millions of options in under a second and got a decent result. The algorithm didn’t need to be smart; it just had to get to a good answer efficiently.

Example: After a couple of years of working professionally I realized that I can solve things quickly at work not because I’m smart, but because I played around with and eliminated lots of things in my free time that didn’t work.

Forecasting models keep track of how wrong they are.

If you have two different forecasting models, the best way to compare them is to choose the one that’s the less wrong. In order to improve your own mental model of how the world works, you need to make predictions and keep track of how wrong you are.

OK, that might sound a little weird. Consider this: when’s the last time you were surprised by something? Why were you surprised? Did you expect that something to never occur? If you think something is impossible and it happens, it means your mental model of how the world works is wrong. That’s OK! It means you need to pick a better model.

Surprises are one way of adjusting your mental model, but if they don’t happen enough (like for me), it’s a good idea to make some predictions about things on your own and see how they turn out. I started doing this with all staff meetings to improve my mental model of how startups work.

Example: Every all staff meeting I take as many notes as possible and try to understand everything that’s going on. And then I make a prediction or several. If we’re trying something new, I try to predict the outcome. I try to predict where the company will be in a month, a quarter, a year, etc. Eventually that time comes and I get to see if I was right about anything, what I was wrong about, and what I didn’t expect, and my mental model of how a startup works improves.

Applying forecasting techniques to design

For a long time I got stuck on learning design because I tried to figure out the right answers. I got a lot more productive when I started treating design like a forecasting problem. It’s simple: good design comes from trying lots of different things and picking the best option. Trying different things is easy. The hard part is figuring out what looks good! So the way I’m learning design right now is always paying attention to what looks good and what doesn’t, and updating my mental model for design. Eventually I’ll have a mental catalog of things that work, and just reuse them!